Unbinding

Rosh HaShanah 5780

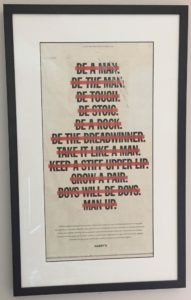

At home we have a framed full-page ad from the New York Times, November 19, 2017. The ad, placed by Harry’s, a shaving-supply company, features a long list of sayings associated with manliness – “Be a rock,” “Take it like a man,” “Man up” – each crossed out with a thick red line. That single sheet of newsprint was taped to our kitchen wall for a year and a half and for me, at least, took on a powerful significance: a daily kavvanah, a framing thought, a challenge to think carefully about how I move through the world as a man. When we moved just after Pesah, Rebecca figured if we didn’t get the ad framed it would eventually disintegrate, so there it is.

Below the main image, the ad begins, “If 2017 has taught us anything, it’s that we need to rethink what it means to be a man.” If we go a step further, is “manliness” even a category that matters anymore? Or is it an outmoded relic of a binary gender system, an idea whose time has passed? As much as I would love to give an unqualified “yes,” that we should be raising our children to value compassion, strength, loyalty, and other virtues regardless of their gender, in reality the established gender types are going to be around for a long time. So while we need to teach our children and students different, more open and flexible ways of thinking about gender for the future, we also need now to reform the gender structures already in place.

2017 has come and gone, and we’re still deep in questions asking us to reappraise what it means to be a man. This is a profoundly difficult task, in two different ways. First, because men’s social and political privilege is so deeply ingrained in the fabric of society that seeking it out is like asking a fish to see the ocean – its very pervasiveness makes male privilege almost invisible. At the same time, the work needed to see and begin to dismantle that privilege also forces us to reckon with the painful consequences of messages like the ones in the Harry’s ad – consequences both physical and emotional, affecting adults and children of all genders.

Both sides of this problem were brought home for me recently when I received an early copy of Joe Buchanan’s new album, Back from Babylon. If you’re not already familiar with Joe Buchanan, you should check him out – he’s one of my favorite contemporary Jewish musicians, blending prayer and Torah with a classic Country sound. Back from Babylon is a spectacular record, but there is one song in particular that I can’t let go of, sometimes listening to it three or four times in a row. In “The Unbinding,” Joe tackles the core story of this morning’s Torah reading: Akedat Yitzhak, the binding of Isaac. I invite you to open your mahzorim to page 103 and follow along as we go through it.[1]

Our Sages didn’t pull any punches; today’s Torah reading is one of the most difficult, enigmatic, demanding stories in the entire Bible. It speaks in silence; the story leaves out far, far more than it ever tells us. Right from the opening words, the questions begin to pile up: “Some time afterward,” or, as Robert Alter puts it more literally, “After these things.”[2] After what things? If we just work backward, there are plenty of options – almost too many! After Abraham sent Hagar and Ishmael into the wilderness? After Sarah gave birth to Isaac, their miracle baby? After the destruction of Sodom and Gomorrah, and Abraham’s failed attempt to spare them? After the circumcision, and the promises, and the journey? After all of it, the entirety of creation and human history? There is an antecedent to this story, but we’re each left to point in our own directions.

Then, “God put Abraham to the test.” OK, a test – to what end? Any test or experiment seeks to demonstrate or determine something. Here, what does God want to know about Abraham? Why test him now, after all “these things” that Abraham has already gone through with God?

And what of Abraham’s response, הנני, “Here I am?” It’s hard to imagine God unaware of Abraham’s location. Rather, הנני indicates what literary scholar Erich Auerbach calls a “moral position,” defining Abraham’s relationship to God.[3] And yet we’re still unsure of what Abraham means with that one concise word, הנני. Indeed, presence, or lack thereof, will keep surfacing in our story – Abraham’s presence, God’s presence, Isaac’s presence. The narrator keeps us posted on their movements, but the more we know about their physical location, the less it seems we know about their emotional state.

All of that, in just the first verse. The second verse cuts right to the point: “Take your son, your favored one, Isaac, whom you love… and offer him there as a burnt offering.”[4] The chain of adjectives ratchets the tension higher with each word – in the same breath that Abraham is being asked to sacrifice his son, God reminds him of the parental relationship; of Isaac’s being Abraham’s sole heir;[5] of his love for the son who was beyond his dreams.[6]

Notice, in the next verse, as Abraham prepares for the journey, that Isaac is referred to as “his son Isaac.”[7] We know who Isaac is, and yet at every possible occasion the narrator will label Isaac as “son” and Abraham as “father,”[8] constantly raising the stakes. Just as Auerbach described הנני as a depiction of Abraham’s “moral position” with respect to God, these words, “father” and “son,” describe more than just a familial tie: they indicate a moral relationship, establishing specific expectations that the characters will – or won’t – fulfill.

The details of Abraham’s preparations raise yet more questions. He takes two servants along, but we know nothing of their role; the next we hear of them is when Abraham leaves them behind. He splits the wood at home and then hauls it for three days across the wilderness, which none of his companions thinks to question.[9] They leave the servants behind, Isaac carrying the wood while his father carries fire and knife, and only then does Isaac speak. He calls out one word, “Father!” and here our translation lets us down; where the English text says, “Yes, my son,” the Hebrew is the very same הנני that Abraham used in response to God.[10] הנני בני, “Here I am, my son,” Alter has him say. Here I am, and I want to scream, Really? Yes, you’re standing there next to your son but where are you? What are you thinking? What is all of this to you? Where do you think this is leading, in the end?

Questions upon questions. When they leave the servants, the Torah tells us, וילכו שניהם יחדיו, “the two walked off together.” Isaac asks his one, painfully simple question, “Where is the sheep for the burnt offering,” and after Abraham’s dodgy answer – “It is God who will see to the sheep” – the Torah says again, וילכו שניהם יחדיו, “the two walked off together.”[11] In such a sparse story, why repeat that they walked together? What kind of “together” is this? Can we accept the traditional suggestion that they went together in heart and mind, united in shared purpose?[12] Dare we suggest that the Torah emphasizes their walking together, in body, to imply that they were not together in spirit?

Akedat Yitzhak is like Biblical quicksand – the deeper we look, the more entangled we become. The characters hardly speak and the little they say only further obscures their true feelings and motives.[13] Three times a character calls out to Abraham – God, Isaac, and God’s messenger – and all three times Abraham answers, הנני, “Here I am.”[14] But does he mean the same thing each time? “Here I am” – in what sense? We’ve seen Abraham speak his mind to God, worried about who will carry on his legacy or outraged at the thought that God might destroy the righteous along with the wicked – but his הנני, “Here I am,” gives no indication of what’s on his mind now. In dealing with Sarah, or his nephew Lot, Abraham shows awareness and understanding of their concerns and emotional needs; whereas here, with Isaac, he seems detached, dispassionate. With the messenger, aside from הנני Abraham is almost entirely unresponsive. He looks up, sees a ram caught in the thicket, takes it – all without any expression of feeling. What goes through his mind at the end, when God’s messenger stops him from the unspeakable thing he felt compelled to carry out? Disappointment that he was thwarted from serving what he took to be God’s will? Horror at what he attempted? Regret that he didn’t speak up for his son the way he tried to defend the strangers in Sodom and Gomorrah? We never hear.

And finally, what are we to make of the messenger’s blessing? “Because you have done this and have not withheld your son, your favored one” – your only one – “I will bestow My blessing upon you.”[15] On the surface this would seem to suggest that, whatever the test, Abraham has passed; and yet the substance of the blessing merely repeats what Abraham was already promised. Moreover, his return home hardly seems like a victory march. He returns to his servants alone, and spends the remainder of his life estranged from the people closest to him. His wife, the next we hear of her, is dead; neither God nor Isaac ever speak to Abraham again; his other son, Ishmael, has already been banished. Out of a lifetime of relationships, only his servants remain.

From this minefield of unanswerable questions emerges Buchanan’s “The Unbinding.” Sung from Isaac’s perspective, the song lays bare the pain of a father’s emotional absence:

Fathers, please unbind your sons.

’Cause the pain that you’re pourin’ they’ll drink

Until they’re gone.

And you won’t see the bruises,

and you won’t see the wounds.

’Til you beat it out of them

just like the world did to you

Fathers, please, unbind your sons.

If we’re going to rethink what it means to be a man, let’s start here, with what might be the Bible’s most challenging story of fatherhood. I haven’t done a thorough check, but I can’t think of another story in the Torah that leans as heavily on that relationship as Akedat Yitzhak, with its drumbeat of “His son,” “His father,” “His son,” “His father.” My heart breaks for this man and this boy – or maybe it’s two men,[16] depending on how you read – alone together. Despite the blessing at the end, I can’t shake the feeling that Abraham failed to grasp the nature of this test.

I don’t think we can understand what it means to be a father without also considering the question of what it means to be a man; for children of all genders who grow up with a father in the home, the father will be the primary example of manhood. And although we all have role models and mentors, of all genders, beyond our parents, when it comes to our other influences – friends, coaches, teachers – they inevitably come later, reinforcing or challenging whatever notions of masculinity we have already absorbed. So for me, the heavy emphasis on Abraham as father and Isaac as son says that this test had to relate in some way to that fundamental relationship – and Abraham missed that critical piece.

We get a lot of different images of God from our tradition, from our prayers as well as from the Torah: king, judge, shepherd, father, and countless others. In some ways God can come across as judgmental, punitive, exacting; at other times, gentle, compassionate, loving. I’m going to make a sweeping claim, and over the holidays I want you to check me and see if I’ve got this right. Wherever the Mahzor uses the metaphor of God as “Father,” it will always be an image of tenderness and compassion. Always.

In one of the special lines we add to the Amidah during the Ten Days of Teshuvah, we refer to God as אב הרחמים, “Compassionate Father.” אבינו מלכנו, one of the signature prayers of this season, addresses God as our Father and our Sovereign – and paints a picture of a Father who is strong in defense of others who are weak and vulnerable; a loving figure who is forgiving, kind, and sympathetic. After each Shofar blast, as we sing together היום הרת עולם, we ask God to be compassionate with us as a father is compassionate with his children, רחמינו כרחם אב על בנים. And in one of the most touching verses of the Musaf Amidah, the prophet Jeremiah quotes God declaring, “Is not Ephraim My dear son, My precious child?” before the verse concludes, רחם ארחמנו, “I always feel compassion for him.”[17]

Think about the images of so-called “manliness” in the Harry’s ad – where is the compassion, the sensitivity, the kindness that the Mahzor portrays as characteristic of a father? Where is any feeling at all? Our tradition offers a very different model of fatherhood – and, by extension, manhood – by consistently portraying our Divine Father as attentive, caring, nurturing, sensitive. I’m not entirely comfortable with the default masculinity of our metaphors for God – one of the things I find powerful about Kabbalah is its broader imaginative palette that encompasses feminine as well as masculine manifestations of God, and I have found new inspiration as egalitarian communities incorporate feminine names and metaphors into our prayers and practices. Still, the image of God as Father that has come down to us through tradition offers a compelling model for us to emulate and a striking critique of western assumptions about masculinity. No doubt, God has an angry, judgmental, punitive side as well – but not as a father. As a father, God comes to us from a place of compassion, protection, love, sensitivity. And Abraham misses this completely. He says, again and again and again, הנני, “Here I am,” but in the song Isaac is left to wonder, “Where are you?”

The 16th-century Italian Rabbi Ovadiah Sforno provides a startling window into what’s going on with Abraham. In explaining the “test” that the very first verse alludes to, he suggests that God knew that Abraham possessed the qualities of love and fear, אוהב וירא, but wanted to see Abraham put these qualities into action.[18] When it comes to the messenger’s blessing at the end of the story, however, Sforno imagines the messenger saying: “Now I know that you fear God in action just as God already knew you feared God in spirit.”[19] The first time I read that line I was stunned, and had to go back again to be sure I hadn’t misread it. Sforno presents the test as being about love and fear, and just a few verses later he describes Abraham only as ירא, God-fearing, saying nothing about Abraham’s quality of אוהב, loving. The omission can only be deliberate and is all the more striking because Abraham is typically viewed as the paragon of loving kindness for his hospitality and outreach. Although he never says so explicitly, Sforno seems to suggest that Abraham at least in part failed God’s test – he proved that he would comply with God’s command, no matter the cost to himself or anyone else; but he failed to show his son, his favored one, the one he loved, Isaac, the compassion he had summoned throughout his life even for total strangers.

I know that you prayed for the lives of men

and an untold number of sons.

And there were not ten, no, there were not ten,

but father, dear, here’s one.

What might Abraham had done differently if he had allowed his love, along with his reverence for God’s command, to guide his choices? Why couldn’t Abraham let that quality, so apparent in his dealings with the outside world, show in his relationship with his son? “Where are you?” Isaac asks in the song. Where are those qualities that are supposed to define you?

Long before psychologists began to study transgenerational trauma, the Bible understood how pain, unacknowledged, gets handed down from one generation to the next. Our story begins אחר הדברים האלה, “After these things,”[20] without letting on which things, how far back we might trace the steps that lead to this moment. We know almost nothing of Abraham’s childhood, except that he was willing to walk away from it entirely, never looking back, losing touch for decades until, at the end of his life, he reaches back out to find a suitable match for his son. Sure, God’s promise of blessing induced Abraham to leave – but he took his nephew Lot with him, and a large household as well; presumably he could have brought his own father, but we have no indication that he even invited him to come along for the journey.[21] Moreover while even estranged sons like Ishmael and Esau return to the family for their fathers’ funerals, Abraham does not return to Haran when his father dies.

While Abraham’s childhood remains an enigma, the Torah shows us other family trauma in grim detail. Just yesterday we read of Sarah asking Abraham to banish his other son, Ishmael; the Torah tells us, וירע הדבר מאד בעיני אברהם, “The matter was evil in Abraham’s eyes,”[22] and yet, with God’s reassurance of divine protection for Ishmael, he goes ahead and does it anyway. Many commentators have pointed out that Abraham insistently argued to save the wicked cities of Sodom and Gomorrah but raised no questions about Akedat Yitzhak – and here is a second instance where Abraham could have protested, could have raised objections or asked for clarification, and instead closes off his feelings and does something that I, as a father, can’t begin to imagine: sending his own child, and the boy’s mother, off into the wilderness to an uncertain fate. What would that experience do to a person? What broke inside Abraham when he woke up early in the morning – just as he does when it’s time to sacrifice Isaac – and gives Hagar, the mother of his elder son, a little bread and water and sends her away?

Of course, we never find out the answer to that question. Whatever Abraham had to shut down in order to cast Ishmael and Hagar out of his house never came back. He couldn’t repress his love for one member of his family without losing his feeling for all of them. So today we read how his pain, held in, denied, suppressed, took its toll on Isaac. Isaac never speaks of the experience; he was a quick study, watched his father conceal all emotion, and hid his own feelings as well. Isaac’s sons, growing up in the shadow of an unspoken trauma, end up at one another’s throats, driving one of them away for twenty-two years. And by the time Jacob and Esau reconcile, Jacob’s own sons have already inherited their share of his pain. “’Cause the pain that you’re pourin’ they’ll drink / Until they’re gone.”

What I find so slippery about this, so difficult to pin down in raising my own children, is that when you look at the litany of damage in the ad, do we really say these things to our kids? Honestly? Sometimes, yeah. Do any of the men in this room, any of the men you know in your life, fully embody this stereotype of masculinity? Probably not. Is there a man here today who does not feel in some way burdened, hurt by this destructive link between “manliness” and emotional repression? I don’t think any of us can get all the way outside its influence.

When Rebecca first hung the Harry’s ad in our kitchen, our son Azzi, five years old at the time, had a lot of questions: “Did anyone ever say those things to daddy?” “Did anyone ever say those things to grandpa?” “Did grandpa say those things to daddy?” I know my grandfather said things like that to my father; I don’t remember my father ever saying them to me. Ultimately, however, he didn’t need to say it outright – I got the message anyway. The society around us, the accumulated history of western civilization, all the social influences beyond the family continually bombard boys and men with a vision of masculinity that binds all of us – boys and girls, men and women and non-binary folk – with suffering and pain. But more than that, I saw it in him and learned at least as much from all that he held back, the emotional distance, the closed-off inner life, as I did from anything he said directly.

“Fathers, please, unbind your sons.” Unbind. At this point it’s no longer enough to end the harmful messages. It’s not enough that I be mindful of not implicitly directing my children into gendered stereotypes. If we hope to spare our children we need to unbind the trauma that has been handed down to us. Abraham may have tied Isaac to the altar, but he had long before bound up his own emotional life, so tight that no gasp of love or compassion could escape. And so he bound Isaac inside just as surely as he bound him outside, bound him in soul as much as in body. Isaac bound Jacob, in his own way, and Jacob bound his own sons, and with each successive knot another generation of pain.

It’s no longer 2017, but we still need to rethink what it means to be a man. This binding, the pain that men hand down to their children and inflict upon their partners, causes protracted harm not only within the family but in our wider world as well. I can’t think of a single issue we struggle with today – gun violence, partisan fracturing, racism, mental illness, homophobia and transphobia – where the binding trauma of masculinity is not at least a factor. It affects all of us, but it is men, and especially fathers, who must do the core work to make things right.

[1] The story appears in Genesis 22.

[2] Gen. 22:1.

[3] Erich Auerbach, Mimesis: The Representation of Beauty in Western Literature, tr. Willard Trask (New York: Doubleday Anchor, 1957), 6.

[4] Gen. 22:2.

[5] Cf. Alter’s translation and commentary on this verse; the word יחידך, translated here as “favored,” literally means, “your only.”

[6] See, e.g., Rashi, Gen. 22:2; Robert Alter, The Five Books of Moses (New York: W.W. Nortion, 2004), commentary to Gen. 22:2.

[7] Gen. 22:3.

[8] Alter, commentary to Gen. 22:3.

[9] Gen. 22:3-5.

[10] Gen. 22:6-7.

[11] Gen. 22:6-8.

[12] Rashi and Radak, Gen. 22:8.

[13] Auerbach, Mimesis, 8.

[14] Gen. 22:1, 7, 11.

[15] Gen. 22:16-17.

[16] There is a midrashic tradition that Isaac was 37 years old at the time of the Akedah; see, e.g., Bereshit Rabbah 56.8.

[17] Jeremiah 31:20; translation from Mahzor Lev Shalem, 161.

[18] Sforno, Gen. 22:1.

[19] Sforno, Gen. 22:12, emphasis added.

[20] Gen. 22:1.

[21] While the Torah announces Terah’s death before God calls Abraham to leave for Canaan, a careful reading of the ages and chronology in the story shows that Abraham in fact left Terah’s household sixty years before Terah’s death (Nahum Sarna, JPS Torah Commentary, Gen. 11:32).

[22] Gen. 21:11.