Recovering Ourselves

Rosh Hashanah 5779 / 10 September 2018

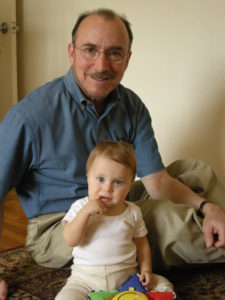

Some of you had a chance to know my dad, Murray Friedman ע”ה, who passed away during Pesah, or may have heard stories while I was sitting shiva. He was the paradigmatic elder, a storyteller and a quiet well of wisdom at the heart of the family. In his retirement, he devoted the last twenty-five years to building and strengthening some of Atlanta’s core Jewish educational institutions, including Camp Ramah Darom and the Weber School. And he loved being a grandfather; earlier in the year, as my sisters and I gathered pictures for a 50th-wedding-anniversary tribute, it struck me that in most of my pictures of him with my kids, he’s sitting on the floor surrounded by toys and smiling.

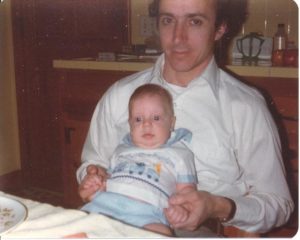

But there is an earlier chapter to his story, one that I tell less often. A story so different it sometimes feels to me like I had two altogether different fathers. I remember, as a young child, wanting to be with my father more than anything. Among my earliest memories, he took me camping at Stone Mountain every three weeks or so, all summer long; barely half an hour from home, we would sleep in a tent and cook oatmeal for breakfast over a campfire. By the time I was in first grade, however, all that had ended. To this day I remember how it felt expecting to see him in the chapel for my Siddur Presentation ceremony, only to have my mom arrive alone and inform me that he had left that morning for a business trip to Brazil. Among the things I learned in elementary school: don’t expect dad at things. Assuming he was in town, he was probably at work; and on those times he showed up, you never knew what to expect. The sweet memories fight for space amid all the times he was impatient, angry, cold and distant.

The summer after my bar mitzvah, after a decades-long struggle with addiction, my father went into recovery. On these ימים נוראים, Days of Awe, we often talk of free will and our ability to change. I don’t question the existence of free will, or its importance, but we also know more about the biology of addiction and the ways that our earliest experiences, long before any concrete memories, leave an imprint that shapes our beliefs and actions. It can be difficult to see these imprints head-on — like trying to see eyeglasses as you are wearing them. Without a mirror, we only see blurry, partial images far out at the margins of our vision.

It’s nice to think we could come to shul for a few hours, sing along with the congregation, listen attentively to the sermon, thump our chests a few times, and go start the new year fresh. Sadly, we all know it’s not that simple. Assuming we have made a clear and honest assessment of where we are in life and what we wish was different — no small feat in itself — our desire for change runs up against habits of action and mind reinforced by years of experience. We see the world in ways whose roots run back to our first years. Even if we could wind back those patterns faster than they were laid down, how many years would it take for me to follow those roots all the way back to the beginning? And that question presupposes a firm commitment to make change, which is also a tall order.

The musaf prayers for Rosh HaShanah offer us a framework for tackling the hard work of teshuvah. Divided into three sections, each built around ten biblical verses, the musaf Amidah walks us through the necessary steps to make real change in our lives.

The first section, מלכויות (malkhuyot, “Sovereignty”), highlights verses that describe God as a king or ruler. It contains the grand Aleinu, in which the prayer leaders — and, in some congregations, the entire community — prostrate themselves on the floor before the open Ark. The whole vibe is God-so-big-me-so-small, and yet I don’t think that’s the total picture.

You will not be surprised to learn that I was very nervous when I interviewed for this job. I had a good feeling about BZBI as a congregation, and Philadelphia seemed like the kind of place I would enjoy living. I really wanted this job. (Thank you, by the way. It’s been great so far.) I arrived on a Thursday evening, consumed with anxiety, and called my rebbe, Reb Mimi Feigelson, to share my feelings with her. After listening sympathetically, she told me, before beginning the interview weekend, to meditate on the psalm of the day for Friday, Psalm 93. I was taken aback: that Psalm begins, ה’ מָלָךְ גֵּאוּת לָבֵשׁ, “God reigns, clothed in pride.” But Reb Mimi explained that, as beings created in the Divine Image, we have times when it is appropriate — necessary, even — for us to take on a regal bearing, to walk in the world with pride and an awareness of our own power. I believe we can read the מלכויות section of the Amidah in the same way. While the prayer focuses on God’s power, we should understand that our own faculties are a reflection or echo of that great Divine Sovereign. We, too, have power — power to change even those things that have become ingrained in our nature. מלכויות, the first part of Rosh HaShanah musaf, invites us to inhabit that power.

We move from there to זכרונות (zikhronot, “Remembrances”), whose verses depict a mindful and attentive God, always looking out for humanity. The core message focuses on God’s seeing us in each moment, recognizing who we are and how we choose to live, waiting and even calling us to return in teshuvah. Our liturgy presents us with a God who knows all things, sees beyond our masks and pretensions. Such scrutiny could feel deeply uncomfortable, but the verses consistently portray God’s benevolent attention. Each instance evokes a memory of a time when God remembered our faithfulness, our love, the eternal covenant binding us with our Creator. The three prophetic verses, in particular, drive home the message that God remains waiting, always, for our return to righteousness. As with מלכויות, here too we can adopt a version of this divine characteristic. While we can’t know others with such perfect clarity, we can know ourselves deeply and truly — if we open ourselves to that possibility. The זכרונות section of musaf invites us to see ourselves as we truly are, giving us a starting point from which to launch our teshuvah.

The third and final section of Rosh HaShanah musaf, שופרות (shofarot, “Shofar blasts”), carries the most important message of all. Its verses, coupled with the hundred shofar notes we will hear in the course of this morning, focus our attention on the day’s most distinctive symbol. The clear, sharp blast is at once immediately perceptible and also largely intangible. You can’t miss the sound, but you also can’t touch it, feel it, hold on to it in any way. It is here and then gone; we only have it in the moment.

If you have a friend or relative walking the twelve step path, you’ve probably heard the mantra: “One day at a time.” It speaks to the difficulties of recovery, and really of any teshuvah process. If we look at the whole picture at once — all the problems in our lives, all the obstacles to improvement, the innumerable years ahead of us in which we need to maintain our teshuvah — almost anyone would give up. It’s too much. Recovery works when the alcoholic says, “I’m not going to drink today.” Teshuvah works when we say to ourselves, “I’m not going to gossip today.” “I’m not going to yell at my kids during breakfast this morning.” “I’m not going to peek at my phone during meetings for the next five minutes.” For teshuvah to work, we need to see it as a life-long process pursued moment by moment.

There’s not much I can do about my whole life; the past is gone, and the future — whatever it will hold — hasn’t arrived yet. But today is always available right now. Pay attention, when we return to the service: how often do you hear the word היום, “today,” in our prayers? The shofar calls us to the present, right here this minute. The broader message of Rosh HaShanah reminds us that the only time we can ever act is right now, and so our teshuvah must happen in each present moment.

In talking about teshuvah, I have deliberately avoided the common English translation, “repentance.” The word “repentance” comes from the Latin paenitentia, which means to regret something or to feel insufficient or unworthy. The penitent feels that something is wrong with him, that he lacks some fundamental goodness. Although Teshuvah also begins with regret, it leads in a very different direction. Based on the Hebrew root ש.ו.ב, teshuvah conceives of change as an act of return. Take a moment to think about the implications: if we do teshuvah after we have done wrong, and teshuvah is an act of return, then a human being’s intrinsic natural state must be good. Unlike the penitent, the person engaged in teshuvah need not feel insufficient; she has deviated from the right path, but her essential nature remains pure. Rather than becoming a completely new person, teshuvah calls us to rediscover our true self.

The day my father died, our family gathered with the rabbi who would officiate at his funeral. After walking through the service, we began to share: early memories from my mom and uncles, recollections of my dad as a father and grandfather from my sisters and I. When the conversation turned to my dad’s career, my mom called for a woman named Joan, who had come to be with us in my dad’s final days. Joan had been my father’s executive assistant for more than twenty years at the Coca-Cola Company, transferring with him from department to department. Listening to her stories brought to mind many conversations we had about mentorship and the leader’s role in supporting others’ success. Suddenly I saw my father so clearly: all the things I admired in him, his commitment to mentoring young Jewish leaders, his unflagging support for my rabbinic career, the seemingly limitless individual attention he showed his grandchildren, were part of him all along. This wasn’t exactly news to me — my dad told many stories from his working years, and my sisters and I knew the basic plot line for most of the stories Joan told — but something about hearing all of him described all at once, working and retired, before recovery and in recovery, brought it together for me. I saw my dad’s teshuvah: his years of hard, painful work to return, to become more fully the person he had always been.

I have two very clear, very early memories of my father, from around the time I was four or five. I hadn’t forgotten them, exactly, but they had slipped away into the recesses of my mind until about a year or two ago. Azzi was going through a phase where bedtime became a multi-step process; Rebecca or I would put him to bed, only to hear him call for us to come back four or five times in the next half hour. His sheets came untucked. He needed water. It was too dark. It wasn’t dark enough. And so on. All of this typically occurred at the exact time that Rebecca and I sat down (finally) to eat dinner. And then I had to get up from the table to settle Azzi into bed — again.

I have two very clear, very early memories of my father, from around the time I was four or five. I hadn’t forgotten them, exactly, but they had slipped away into the recesses of my mind until about a year or two ago. Azzi was going through a phase where bedtime became a multi-step process; Rebecca or I would put him to bed, only to hear him call for us to come back four or five times in the next half hour. His sheets came untucked. He needed water. It was too dark. It wasn’t dark enough. And so on. All of this typically occurred at the exact time that Rebecca and I sat down (finally) to eat dinner. And then I had to get up from the table to settle Azzi into bed — again.

Walking up to his room, I could feel the rage bubbling up to the surface — and then suddenly I saw myself at his age, getting up from bed for whatever reason. The way our house was laid out, my father had a direct line of sight from the chair in his bedroom where he would watch TV all the way to the door of my room, and I could hear him yelling, from the far side of the house, “Get back in that bed!” All the feelings came back to me, what it felt like to be that small boy who needed something and was pushed away, rejected without consideration. With Azzi still calling out for me, I sat down on the stairs and began to cry. The frustration and anger I felt were the same things I heard in my dad’s voice all those years ago, and I cried for myself, for being that boy who needed his father so desperately, for Azzi and the ways I must have been treating him at bedtime, for my father’s emotional imprint on me that I was now handing down to him.

Then, as I cried, another memory came: lying in bed tucked under blankets, the only light coming from the hallway through a half-open bedroom door, my father sitting on my bed and singing. In my memory he sang seven or eight songs — old lullabies, silly rhyming songs, German folk songs he picked up in the army — way more songs than he ever would have sung at any one time, but all songs I remembered him singing to me as a kid. As I sat there on the steps with these two visions, I understood that both of these memories were true of my dad. Both had left their imprint on me, setting up default patterns of interpretation and response. Now, I had the opportunity — and, perhaps, the responsibility — to choose among them.

As my crying subsided I resolved to take a minute for my anger to pass whenever Azzi needed me after bedtime. I would wait to go in to him until I could respond with compassion. In choosing for myself how to act, I could also choose for him: to imprint one of those memories of my dad, patient, singing, loving, and leave out the other. I’ve had mixed success, as you would imagine, but overall I succeeded in changing how I respond to my children. Keeping my two bedtime memories of my dad present in my mind helped me stay focused on my goal, relating to them with care, compassion, and nurturing attention.

In doing Teshuvah, we return to a core part of ourselves. Often, we’re going back to a place so deep it feels like discovery, or perhaps rediscovery. Ultimately, teshuvah asks us to make an intentional, selective return — choosing which parts of our starting pattern we want to emphasize and live through, and which parts we would like to alter or leave behind entirely. Even as I continue working on patience at bedtime, I keep encountering new choices about how to live. This way of pursuing teshuvah requires slow, painstaking attention. It forces us to confront intense pain, but also opens the door for healing and reconciliation. Our choices about what to leave behind and what we will maintain may be our only means of soothing past hurt. They also help us keep the ones we love most present in our lives. Each time I snuggle up with a kid to read a book or sing a bedtime song, I think about my dad, and feel his presence with us as well.

That is the essence of this day, of this season. Rosh HaShanah guides us in owning our power to make change, even when it proves difficult; seeing ourselves with loving clarity, so we can make conscious choices about how we will move forward; and staying focused on the present moment, the space in which we have real ability to act.

I always felt these last twenty-five years with my dad were a gift. I now see the ways in which that gift runs much farther than I had previously understood. His teshuvah opened new doors for me to choose how I will live. Through his example, I came to understand that our most important work is to find that best, truest self within us and bring it into the world. And in continuing that quest for myself, in a sense continuing the work he started, I hand that gift down to my children as well.